Стр. 169

"И

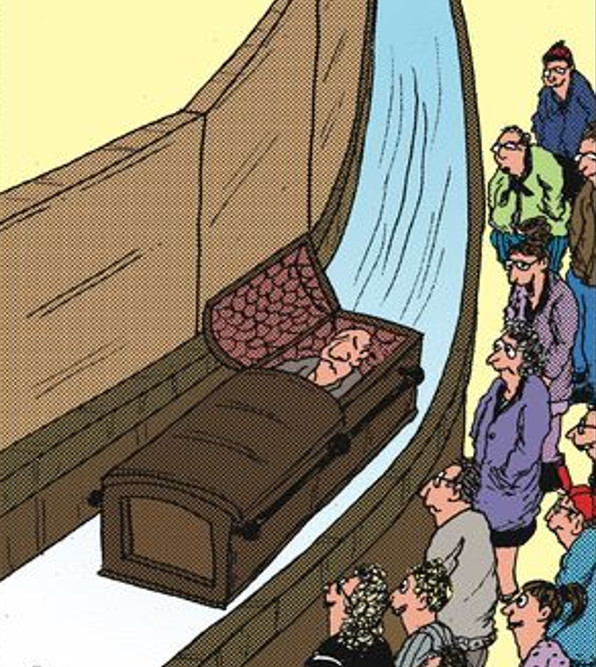

наконец, однажды, когда его время на Земле заканчивается и он чувствует

постукивание Смерти на своём левом плече, его Дух-Spirit, кто всегда

готов, летит к месту его выбора и там воин танцует до самой смерти...A

Man of Knowledge knows, that death is the last witness, because he

Sees...Никто не может быть свидетелем этого танца, только Смерть может

быть."

(Перед

Смертью танцует энергетическое тело воина или его Дух, а не физическое

тело! Проще говоря, "НЕ ДЕЛАНИЕ" -

это

детали того мира, который мы не видим, нам его не показывают! Но если

передвинуть нашу Точку Восприятия в нашем энергетическом Коконе на

определённое место, то тот мир мы увидим! ЛМ.)

стр. 207

"Can you

see Lines of the World and touch them?"

"Let's say, that

you can feel them. The most difficult part, about the warrior's way, is

to realize, that the world is a feeling. When one is not-doing, one is

feeling the world, and one feels the world through its lines."

"Самые долговечные Линии,

которые Человек Знаний производит, создаются из середины тела," сказал

Дон Хуан. "Он также может создать их своими глазами."

"Они реально - Линии?"

"Конечно!"

"Ты можешь их увидеть и потрогать?"

"Скажем, что ты можешь их почувствовать. Самая трудная часть в пути

воина, это - понять, что мир - это - ЧУВСТВО. Когда ты делаешь "НЕ

ДЕЛАНИЕ", можно чувствовать мир и чувствовать его через его Линии

Мира."

стр. 211

"Замечаниями Дон

Хуана

были: я должен быть рад тем, чего я добился, потому что, как никогда, я

подошёл к делу правильно, что уменьшая мир, я его увеличил и это,

несмотря на то, что я был далёк от того, чтобы чувствовать ЛИНИИ МИРА."

(Сейчас это можно делать

электроникой, на компьютере, например, когда гуглишь карту города.

Чтобы

увеличить больше улиц города на карте, нам приходиться уменьшить все

детали города! ЛМ).

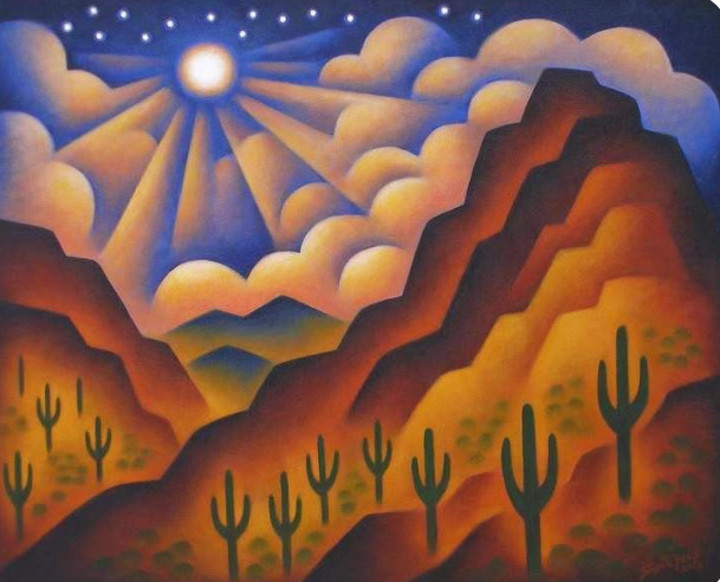

213

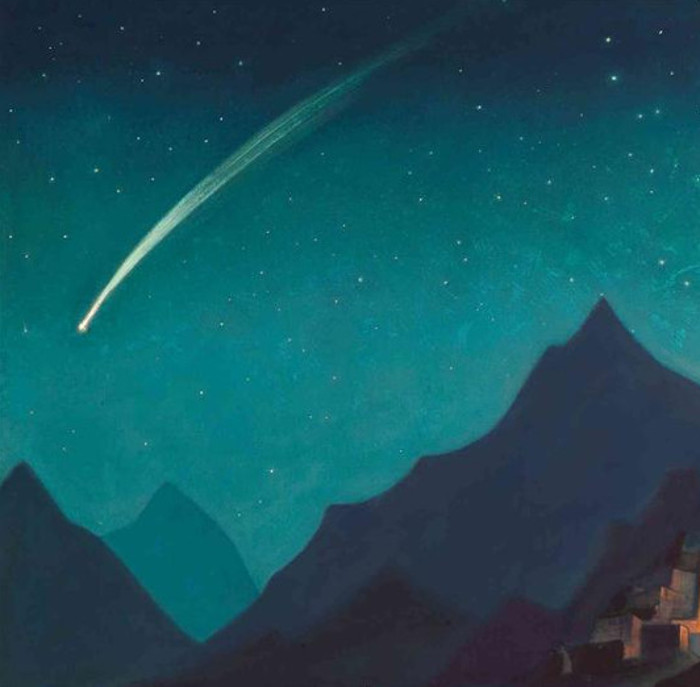

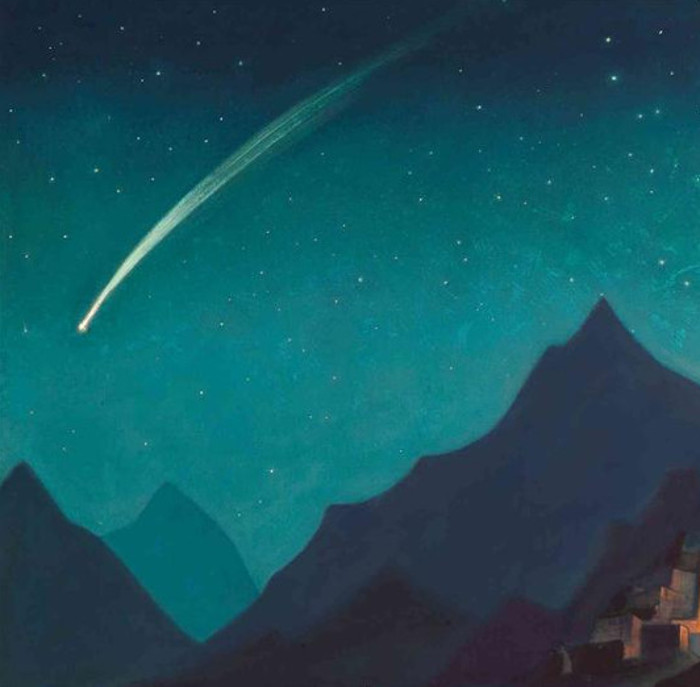

"В течение дня тени

являются дверьми в "НЕ ДЕЛАНИЕ"," сказал он. "Но ночью,

так как "ДЕЛАНИЕ" преобладает очень

незначительно в темноте, всё - в тенях, включая союзников."

"During the day shadows are the doors of not-doing," he said. “But at

night, since very little doing prevails (be the same or current) in the

dark, everything is a shadow, including the allies."

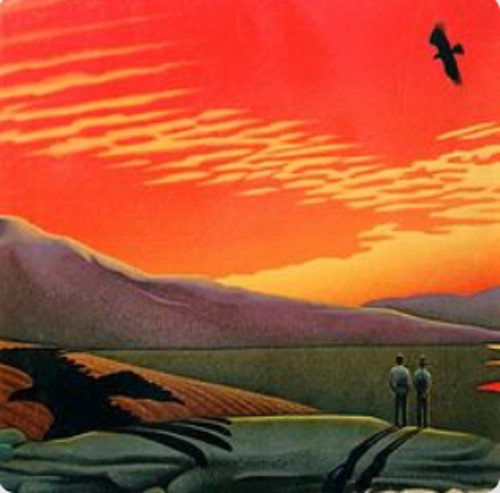

267-269

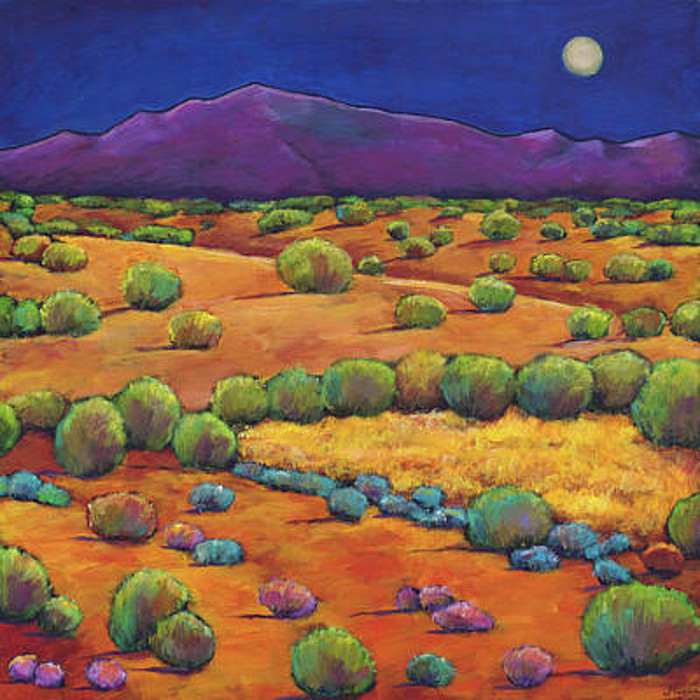

"Я смотрел прямо на

горизонт и затем я УВИДЕЛ "ЛИНИИ

МИРА". Я реально воспринял самое экстраординарное изобилие светящихся

белых Линий, которые пересекали всё вокруг меня.На момент, я подумал, что наверно, я

испытывал солнечный свет,

отражённый моими ресницами. Я поморгал и снова посмотрел:

Линии были

постоянными и были наложены на или пронизывали насквозь всё окружающее.

Я повернулся кругом и осмотрел экстраординарный Новый Мир.

Линии были

видимыми и постоянными, даже когда я не смотрел на Солнце. Я оставался на вершине

холма в состоянии вершины счастья, что показалось мне бесконечным. Я

чувствовал, как что-то тёплое и успокаивающее выходит из мира и из

моего тела. Я знал, что обнаружил секрет: он был таким простым.

Я

испытывал незнакомый поток чувств. Никогда в своей жизни не имел я

такой нереальной вершины счастья, такого покоя, такого охвата и всё же,

я не мог описать обнаруженный секрет словами и даже мыслями, но моё

тело знало это...

"Сегодня

шакалы ничего тебе не говорят, и ты не можешь видеть "ЛИНИИ МИРА". Это

произошло с тобой вчера просто потому, что что-то в тебе остановилось."

"Что во мне могло

остановиться?"

"То, что остановилось

в тебе вчера, было то, что люди рассказывали тебе: как выглядит мир.

Понимаешь, люди с рожденья говорят нам, что мир такой и такой, вот так

и так, и естественно у нас нет другого выбора, как видеть мир глазами

людей, рассказывающих нам о нём." Мы посмотрели друг на друга. "Вчера

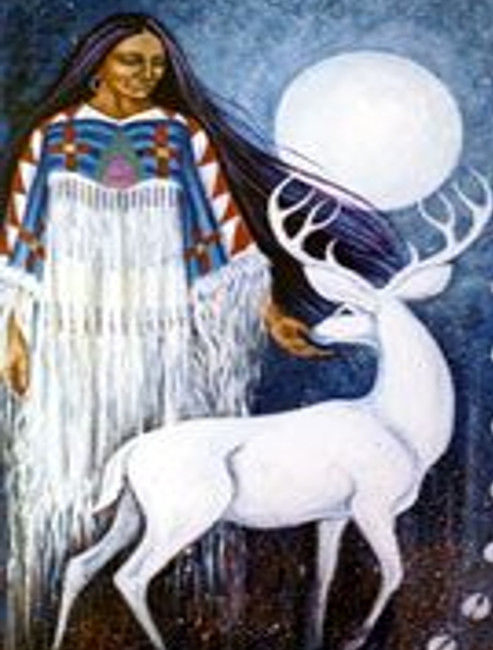

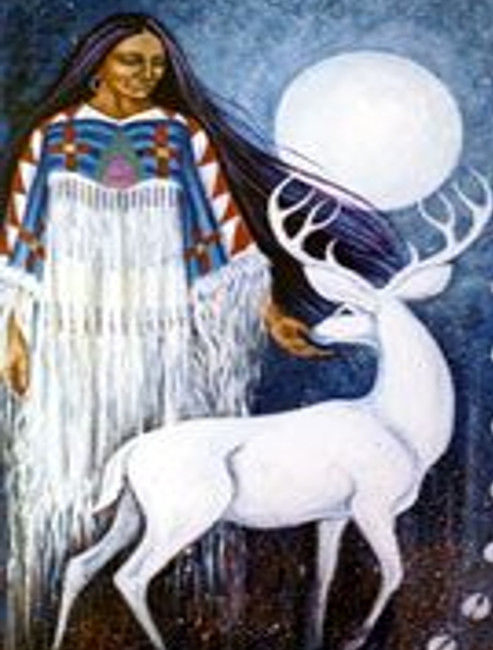

мир стал таким, каким его описывают тебе Колдуны. В том мире шакалы

говорят, и олени, как я тебе однажды сказал, а также змеи, деревья и

другие живые существа.

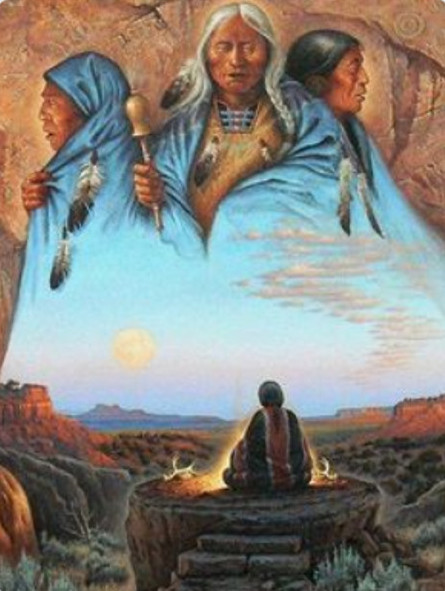

Но что я хочу, чтобы ты научился, это - ВИДЕТЬ. Наверно,

ты сейчас знаешь, что ВИДЕТЬ случается только, когда пролезаешь между

мирами: Миром обычных людей и Миром Колдунов. Сейчас

ты висишь

посредине, между обоими. Вчера ты верил, что шакал разговаривает с

тобой. Любой Колдун, кто не ВИДИТ, будет верить в то же самое, но тот,

кто ВИДИТ, знает, что верить в это - значит точно находиться в Мире

Колдунов. К тому же, не верить, что шакал говорит, значит находиться в

Повседневном Мире, в мире обычных людей..."

"Дон Хуан, ты имеешь

ввиду, что ни мир обычных людей, ни мир Колдунов - не реальны?"

"Они - реальные миры

и они могут действовать на тебя. Например, ты мог спросить того шакала

всё, что хочешь знать, и это заставило бы его дать тебе ответ.

Печально только, что на шакалов нельзя полагаться. Они - проходимцы.

Это - твоя судьба - не иметь надёжного друга среди животных."

Дон Хуан объяснил,

что шакал собрался быть моим компаньоном на всю жизнь, и что в мире

Колдунов иметь друга-шакала считается нежелательным. Он сказал, что для

меня было бы идеальным поговорить с гремучей змеёй, так как они были

превосходными друзьями..."

"Что такое Колдун шакалов?"

"Тот,

кто узнаёт много вещей от его братьев-шакалов." Я хотел продолжать

спрашивать, но он сделал жест, останавливающий меня. "Ты ВИДЕЛ "ЛИНИИ

МИРА"," сказал он. "Ты ВИДЕЛ светящееся Существо. Сейчас ты почти готов

встретить союзника. Конечно ты знаешь, что мужчина, которого ты видел в

кустах, был союзник. Ты слышал его рёв, как гул самолёта. Он будет

ждать тебя на краю поля, к которому я сам тебя возьму."

267-269

"The

Sun was almost over the horizon. I was looking directly into it and

then I Saw the "Lines of the World". I actually perceived the most

extraordinary profusion of fluorescent white lines, which criss-crossed

everything around me. For a moment I thought, that I was perhaps

experiencing sunlight, as it was being refracted by my eyelashes. I

blinked and looked again. The lines were constant and were superimposed

on or were coming through everything in the surroundings. I turned

around and examined an extraordinarily new world. The lines were

visible and steady, even if I looked away from the Sun. I stayed on the hilltop

in a state of ecstasy, for what appeared to be an endless time, yet the

whole event may have lasted only a few minutes, perhaps only as long,

as the Sun shone, before it reached the horizon, but to me it seemed an

endless time. I felt something warm and soothing oozing out of the

world and out of my own body. I knew, I had discovered a secret. It was

so simple. I experienced an unknown flood of feelings. Never in my life

had

I had such a divine euphoria, such peace, such an encompassing

grasp, and yet, I could not put the discovered secret into words, or

even into thoughts, but my body knew it...

"Тoday the coyotes do

not tell you anything, and you cannot

see the Lines of the World. Yesterday you did all that, simply because

something had stopped in you."

"What

was the thing,

that stopped in me?"

"What

stopped inside you yesterday, was what people have been telling you the

world is like. You see, people tell us, from the time we are born, that

the world is such and such, and so and so, and naturally we have no

choice, but to see the world the way people have

been telling us it is."

We looked at each

other: "Yesterday the world became, as sorcerers tell you it is. In

that world coyotes talk and so do deer, as I once told you, and so do

rattlesnakes, trees and all other living beings. But what I want you to

learn is Seeing. Perhaps you know now, that Seeing happens only, when

one sneaks between the worlds, the world of ordinary people and the

world of Sorcerers. You are now smack in the middle point

between the two. Yesterday you believed the coyote talked to you. Any

sorcerer, who doesn't See, would believe the same, but one, who Sees,

knows, that to believe that, is to be pinned down in the realm of

Sorcerers. By the same token, not to believe, that coyotes talk, is to

be pinned down in the realm

of ordinary men...

"You

have seen the Lines of the World," he said. "You have seen a Luminous

Being. You are now almost ready to meet the ally. Of course you know,

that the man you saw in the bushes, was the ally. You heard its roar,

like the sound of a jet plane. He'll be waiting for you at the edge of

a plain, a plain, I will take

you to myself..."

"Do you mean, don

Juan, that neither the world of ordinary men, nor the

world of sorcerers is real?"

"They are real

worlds. They could act upon you. For example, you could have asked,

that coyote about anything you wanted to know, and it would have been

compelled (forced) to give you an answer. The only sad part is, that

coyotes are not reliable. They are tricksters. It is your fate not to

have a dependable animal companion."

Don Juan explained, that the coyote

was going to be my companion for

life, and that in the world of sorcerers, to have a coyote friend, was

not a desirable state of affairs. He said, that it would have been

ideal for me to have talked to a rattlesnake, since they were

stupendous

companions..."

"You

have seen the Lines of the World," he said. "You have seen a Luminous

Being. You are now almost ready to meet the ally. Of course you know,

that the man you saw in the bushes, was the ally. You heard its roar,

like the sound of a jet plane. He'll be waiting for you at the edge of

a plain, a plain, I will take

you to myself."

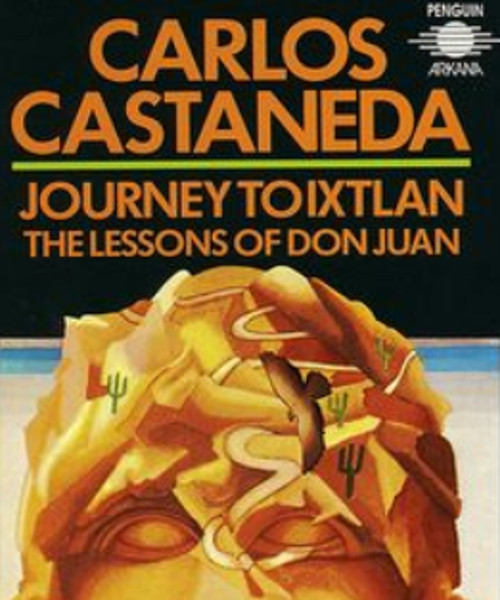

КАРЛОС КАСТАНЭДА "Путешествие в Икстлан"

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

7

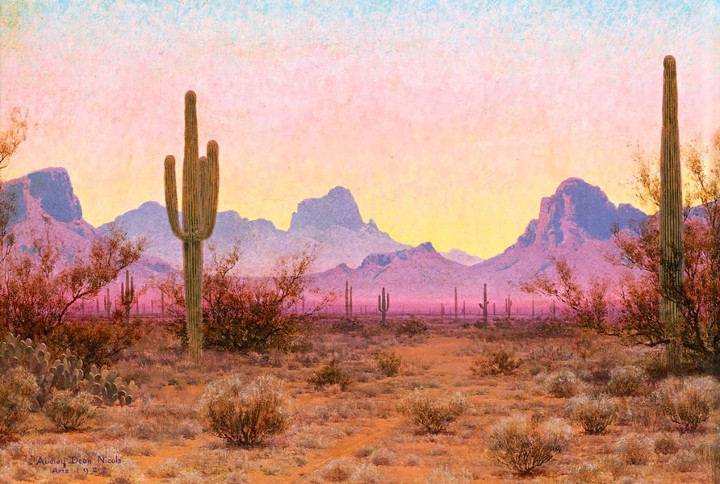

В субботу, 22 мая 1971 я поехал в Сонору, Мексика, навестить Дон Хуан

Матус, Колдуна-индейца Яки, с кем я был знаком с 1961. Я думал, что мой

визит в тот день будет отличаться от множества моих визитов к нему за

эти 10 лет, как его ученика. События, которые произошли в тот день и в

следующие дни, однако, были мимолётными для меня. К тому времени моё

учение подошло к концу. Это не был каприз с моей стороны, а реальное

завершение. Я уже этот случай описывал в моих двух предыдущих книгах:

"Учения Дон Хуана" и "Другая Реальность". Мой основной логикой в обоих

книгах было то, что главное в обучении на Колдуна были состояния

необычной реальности, получаемые после проглатывания наркотических

трав. В этом отношении Дон Хуан был экспертом в использовании 3х таких

растений: peyote или Lophophora williamasii, jimson weed или Datura

inoxia; и вид наркотических грибов, принадлежащих - genus Psylocebe.

Моё восприятие мира через эффекты тех наркотиков было таким

ошеломляющим и странным, что мне пришлось согласиться, что такие

состояния были единственным путём общения и изучения того, что Дон Хуан

пытался учить меня. Такая логика была ошибочна. Во избежание

непонятного в моей работе с Дон Хуаном, я бы хотел здесь объяснить

кое-какие детали.

8-9

До сих пор, я не делал никаких попыток, представить Дон Хуана в

культурном окружении. Тот факт, что он считает себя индейцем Яки, не

значит, что его знания Колдовства известно или в общем практикуется

индейцами Яки. Все разговоры, которые Дон Хуан и я имели в течении моей

учёбы, происходили на испанском, и только благодаря прекрасному знанию

Дон Хуаном этого языка, я получил детальные объяснения замысловатости

его системы верований. Я относился к этой сложной и хорошо

распланированной части Знаний, как к Колдовству, и к нему, как к

Колдуну, потому что те категории он сам использовал в обычных

разговорах.

Так как я был способен записывать большую часть того, что он говорил в

начале учёбы и всё, что было сказано позже фразами, я накопил обширные

записи.

Чтобы те записи можно было читать, и всё же сохранить драматическое

единство Учений Дон Хуана, мне пришлось редактировать их, но что я

пропускал, считал неважным для темы, которую поднимал. В случае моей

совместной работы с Дон Хуаном, я ограничивал свои усилия только для

наблюдений за ним как за Колдуном и получить максимум его знаний. Я

должен сначала объяснить основные верования Колдовства, как они были

даны мне Дон Хуаном. Он говорил, что для Колдуна наш Повседневный Мир -

не реален, а реальность или мир, который мы знаем, это только описание.

Чтобы это доказать, Дон Хуан концентрировал все свои усилия, чтобы

привести меня к подлинному убеждению того, что у меня было в голове,

как наш мир, было просто описание мира; описание, которое вбивалось в

меня с рожденья. Он указал, что все, кто контактируют с ребёнком,

являются учителем, кто без конца описывает мир ему до того момента,

когда ребёнок становится способен воспринимать мир, как его описывали.

Согласно Дон Хуану, у нас нет в памяти того зловещего момента, просто

потому что никто из нас не мог иметь никакой точки, на которую мог

ссылаться, чтобы сравнивать её с чем-то ещё. Однако с того момента

ребёнок - член общества. Он знает описание мира; и его участие

становится полным, я полагаю, когда он способен делать все нужные

переводы восприятия, которые, соответствуя такому описанию,

подтверждают его.

Для Дон Хуана тогда реальность нашей ежедненой жизни состоит в

бесконечном течении воспринимаемых интерпретаций, которые мы -

индивидуалы, кто разделяет специфическое участие, научился делать это

совместно. Идея, что воспринимаемые интерпретации, которые создают наш

мир, имеют течение, гармонирующее с фактом, что они двигаются

беспрерывно и редко обсуждаются. Собственно, реальность мира, который

мы знаем, принимается настолько как должное, что основные принципы

Колдовства, что наша реальность просто одно из многих описаний, с

трудом могут быть взяты как что-то серьёзное. К счастью, в случае моей

учёбы Дон Хуана совсем не волновало: мог я или не мог относиться серьёзно к его

предложениям, и он продолжал просветлять меня, несмотря на моё

сопротивление, моё недоверие, и мою неспособность понять то, что он

говорил. Таким образом, как учитель Колдовства, Дон Хуан отважился

описать мне мир с нашего самого первого разговора. Мои затруднения

схватить его понятия и методы исходили из факта, что его описания были

чужеродными и не согласовывались с моими собственными.

Его утверждение было, что он учил меня как ВИДЕТЬ, а не как глядеть, и

что "Остановить Мир" был первый шаг к ВИДЕНИЮ. Годами, я считал идею "Остановить Мир" чем-то

вреде метафоры, которая реально ничего не значила. Только во время

неформального разговора, который произошёл к концу моей учёбы, я

полностью понял его масштаб и важность, как одно из

главных предметов Знаний Дон Хуана. Дон Хуан и я говорили о разных

вещах в расслабленной манере. Я рассказал ему о моём друге и его

дилемме со своим 9ти летним сыном.

10-11

Ребёнок, кто жил с матерью последние 4 года, теперь жил с моим другом и

проблема была в том, что с ним делать? Согласно моему другу, ребёнок не

уживался в школе; у него не хватало концентрации и ему ничего не было

интересно. Он устраивал скандалы, плохо себя вёл и убегал из дому.

"Твой друг явно имеет проблему," сказал он, смеясь. Я хотел высказать

ему все ужасные вещи, проделанные ребёнком, но он перебил меня. "Нет

нужды ещё говорить об этом бедном маленьком мальчике," сказал он. "И

нет нужды тебе или мне относиться к его действиям в наших мыслях, так

или иначе." Его манера была резкой, а тон твёрдый, но потом он

улыбнулся.

"Что может сделать мой друг?" спросил я.

"Самое худшее, что он может сделать, это заставить этого ребёнка

согласиться с ним," сказал Дон Хуан.

"Что ты имеешь ввиду?"

"Я имею ввиду, что этот ребёнок не должен быть побитым или напуганным

его отцом, когда он не ведёт себя, как хочет его отец."

"Как он может его учить чему-либо, если не будет с ним твёрдым?"

"Твой друг должен позволить кому-то ещё отшлёпать ребёнка."

"Он не может позволить кому-то ещё трогать его маленького мальчика!"

сказал я, удивлённый его советом. Дон Хуан, похоже, получал

удовольствие от моей реакции и хихикал.

"Твой друг - не воин," сказал он. "Если бы он был, он бы знал, что

самая плохая вещь, какую можно сделать, это - угрожать людям напрямую."

"Что бы сделал воин, Дон Хуан?"

"Воин подошёл бы к этому стратегически."

"Я всё ещё не пойму, что ты имеешь ввиду."

"Я имею ввиду, что если твой друг был бы воином, он бы помог своему

ребёнку 'Остановить Мир'."

"Как может мой друг это сделать?"

"Ему нужна личная энергия. Ему нужно быть Колдуном."

"Но он не Колдун."

"В этом случае он должен использовать обычные средства, чтобы помочь

сыну поменять его идею мира. Это не 'Остановить Мир', но это

всё равно сработает."

Я поппросил его объяснить свои идеи. "Если бы я был на месте твоего

друга," сказал Дон Хуан, "Я бы начал с того, что нанял кого-то

отшлёпать мальчишку. Я бы пошёл в трущобы и нанял самого неприятного

человека, какого только можно найти."

"Напугать ребёнка?"

"Не только напугать мальчишку, глупец. Этот малец должен быть

остановлен, а быть избитым своим отцом, не принесёт результата. Если

кто-то хочет остановить наших мужчин, то нужно всегда быть в стороне.

Так всегда можно руководить давлением." Идея была абсурдной, но она всё

же для меня была привлекательной.

Дон Хуан положил свой подбородок на свою левую ладонь. Его левая рука

лежала на деревянном ящике, служащим столом. Его глаза были закрыты, но

зрачки двигались. Я чувствовал, что он смотрит на меня через свои

закрытые глаза. Эта мысль напугала меня.

"Скажи мне больше, что мой друг должен делать со своим мальчишкой,"

сказал я.

"Скажи ему пойти в трушобы и очень осторожно выбрать уродливого

бродягу," продолжал он. "Скажи ему поймать мальчишку. Нужен тот, у кого

ещё осталась какая- то сила." Затем Дон Хуан разработал странную

стратегию. Мне нужно было проинструктировать своего друга иметь

человека и чтобы он следовал за ним или ждать его в месте, куда он

пойдёт со своим сыном. Мужик, в ответ на согласованный знак, данный

вследствии плохого поведения со стороны мальчишки, должен выскочить из

тайного места, схватить ребёнка и хорошенько его отшлёпать. "После

того, как мужик напугает его, твой друг должен помочь мальчишке вернуть

к себе доверие, любым путём. Если твой друг последует этой

процедуре 3-4 раза, уверяю тебя, что этот ребёнок будет чувствовать себя ко всему по другому. Он поменяет

свою идею о мире."

"Что если страх ранит его?"

12-13

"Страх никогда ещё никого не ранил. Что ранит Дух (spirit), это - иметь кого-то

всегда над душой, бьющего тебя, приказывая что делать и что не делать.

Когда этот ребёнок будет более уравновешен, ты должен сказать своему

другу сделать для него последнюю вещь. Он должен найти способ добраться

до мёртвого ребёнка, скорее всего в госпитале или в морге. Он должен

взять туда своего сына и показать ему мёртвого ребёнка. Он должен

позволить ему потрогать труп левой рукой один раз на любом месте,

только не на животе. После того, как мальчик это сделает, он будет

обновлён. Мир уже никогда не будет для него тем же самым."

Тогда до меня дошло: все годы нашего общения Дон Хуан применял ко мне

ту же тактику, правда другого масштаба, которую он предлагал моему

другу использовать с его сыном. Я спросил его об этом. Он сказал, что

старался всю дорогу учить меня, как 'Остановить Мир'. "Ты

пока не остановил," сказал он, улыбаясь.

"Похоже, ничего не помогает, потому что ты очень упрям. Однако, если бы

ты не был такой упрямый, то к настоящему моменту ты бы наверно 'Остановил Мир' любым

способом, которым я тебя обучил."

"Какие способы, Дон Хуан?"

"Всё, что я говорил тебе делать, были способы 'Остановить Мир'."

Через несколько месяцев после этого разговора, Дон Хуан достиг того,

что он наметил сделать: учить меня 'Остановить Мир'. Это

монументальное событие в моей жизни заставило меня пересмотреть в

деталях свою десятилетнюю работу. Мне стало ясно, что моё

первоначальное представление о роли наркотических трав было ошибочным.

Они не были существенной чертой описания мира Колдуном, а только

вспомогательное средство зацементировать, так сказать, части описания,

которые я, иначе, не был способен воспринять. Моя настойчивость

держаться за мою стандартную версию реальности превращало меня почти в

слепого и глухого к целям Дон Хуана. Поэтому это было просто мой

недостаток чувствительности, который культивировал их (наркотических

трав) использование. Полностью пересматривая свои записи, я осознал,

что Дон Хуан дал мне уйму новых описаний в самом начале нашего общения,

что он называл "Приёмы для Остановки Мира".

Я выбросил ту часть своих записей в своих ранних работах, потому что

они не относились к использованию наркотических трав. Сейчас я по праву

восстановил их в общий спектр Учений Дон Хуана и они включали первые 17

глав этой работы. Последние 3 главы записей покрывают события, что

становится моей кульминационной точкой в моей "Остановке Мира".

Суммируя, я могу сказать: когда я начал учёбу, реальность была другой,

имеется ввиду, было описание мира Колдунами, которое я не знал.

ДонХуан, как Колдун и учитель, обучил меня этому описанию. Десятилетняя

учёба, которую я прошёл, поэтому состояла в установлении этой

незнакомой реальности, раскрывая её описание, добавляя больше и больше

сложных частей, пока я шёл вперёд. Остановка учёбы означало, что я

изучил новое описание мира в убедительной и достоверной манере и, таким

образом, я стал способен вызвать в себе новое восприятие мира, которое

сходилось с его новым описанием. Другими словами, я заслужил членство.

Дон Хуан

утверждал: чтобы достичь ВИДЕНИЯ, сначала придётся 'Остановить Мир'.

'Остановить

Мир' и в самом деле было подходящей интерпретацией определённых

состояний сознания, в которых реальность Повседневного мира менялась,

потому что течение интерпретации, которое обычно движется без

остановки, было остановлено чередой обстоятельств, чуждых этому

течению. В моём случае, череда обстоятельств,

чуждых моему нормальному течению интерпретаций, было описание мира

Колдунами. Предвидение Дон Хуана для "Остановке Мира" было то,

что необходимо быть убеждённым. Другими словами, приходится учиться

новым описаниям в полном масштабе с целью противопоставить это старой

версии, и таким образом сломать догматическую уверенность, которую мы

все имеем, что в достоверности наших восприятий мира нет сомненья.

После "Остановки Мира",

сдедующий шаг был ВИДЕНИЕ. Под этим Дон Хуан подразумевал то, что я

хотел бы распределить

по категориям, как ответ воспринятых забот мира, вне описания, которому

мы научились называть реальностью."

14

Моё заявление, что все эти шаги могут только быть поняты терминами

описания, которому они принадлежат; и так как это было описание,

которое он отважился дать мне с самого начала, я должен затем позволить

его учениям быть единственным источником входа в них. Таким

образом я предоставляю слова Дон Хуана говорить за себя.

Часть 1: 'Остановить Мир' -

Подтверждения из Окружающего Нас Мира

17

"Я так понимаю, что вы много знаете о растениях, сэр," сказал я

старику-индейцу передо мной. Мой друг только что связал меня с ним и

оставил комнату, мы представились

друг другу. Старик сказал мне, что его имя было Хуан Матус.

"Это тебе сказал твой друг?" сказал он небрежно.

"Да."

"Я собираю растения или скорее, они разрешают мне их собирать," сказал

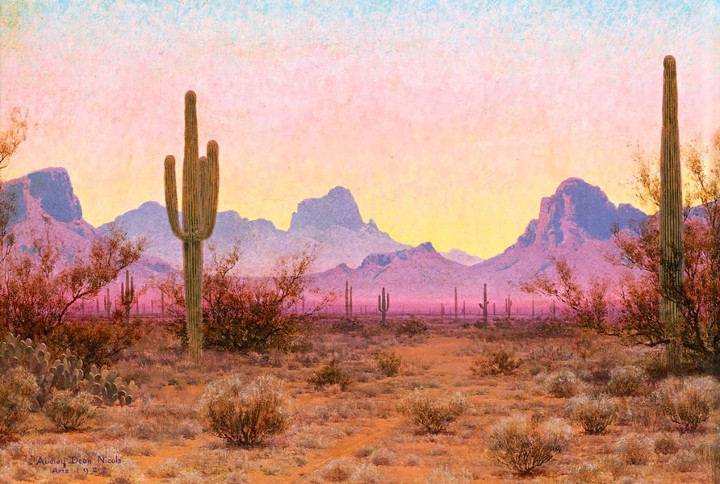

он тихо. Мы были в комнате ожидания автобусного депо в Аризоне. Я

спросил его очень формальным тоном на испанском, если он позволит мне

задать ему несколько вопросов: "Разрешит ли мне caballero задать ему вопросы?"

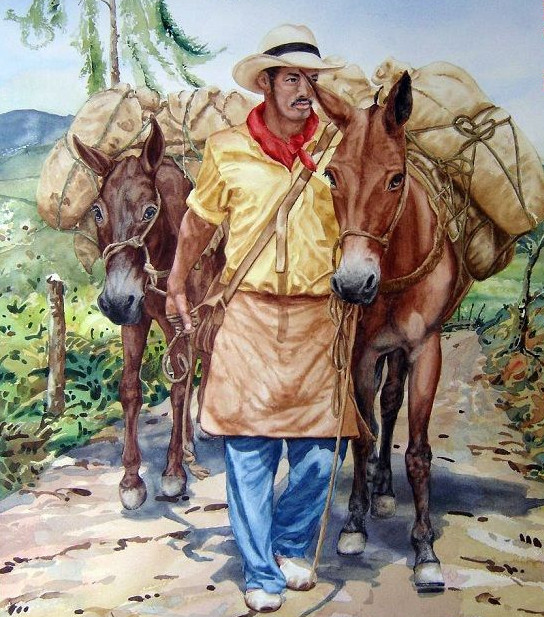

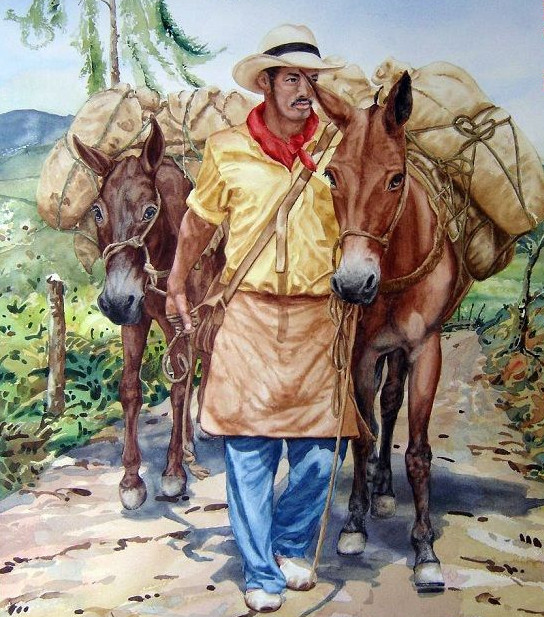

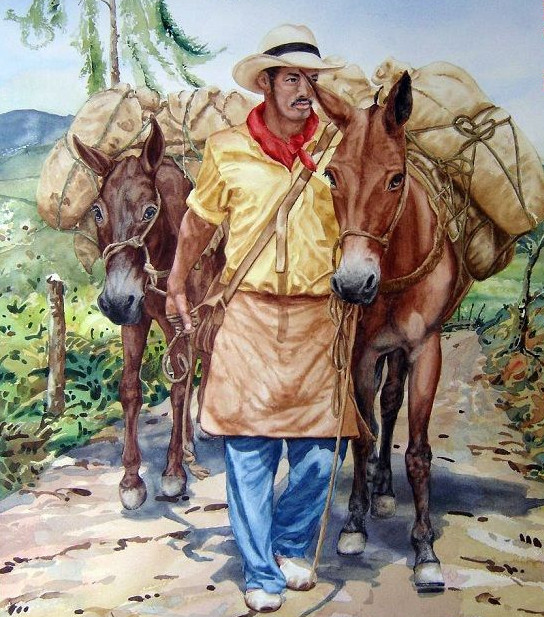

"Caballero," что происходит

от слова "caballo" -

лошадь, раньше означало - наездник или джентлмен на лошади. Он

вопросительно посмотрел на меня.

"Я - наездник, только без лошади," сказал он и широко улыбнулся, затем

добавил, "Я сказал тебе, что моё имя Хуан Матус."

Мне понравилась его улыбка и я подумал, что он явно человек, кто ценит

прямоту, и смело решил прощупать его своим предложением. Я сказал ему,

что был заинтересован в коллекционировании и изучении медицинских трав.

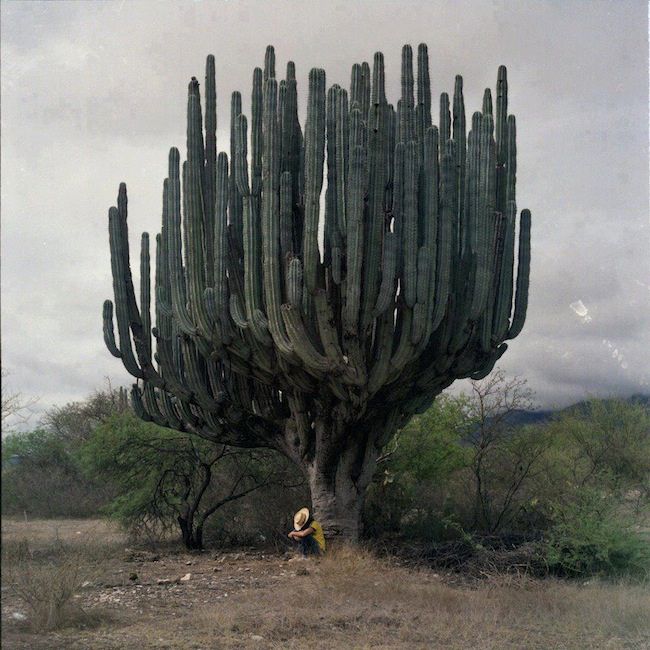

Особенно, мне было интересно использование наркотического кактуса - peyote, который

я долго изучал в университете Лос Анжелеса. Я подумал, что моя

презентация была очень серьёзной. Я был очень сдержан и казался себе

внушающим доверия.

18-19

Старик медленно покачал головой и я, воодушевлённый его молчанием,

добавил, что это несомненно принесёт нам пользу, если мы собирёмся и

обсудим дело с peyote. И

как раз в этот момент он поднял голову и посмотрел мне прямо в глаза.

Это был сильный, незабываемый взгляд. И всё же он ни коим образом не

был угрожающим или сверхестественным. Это был взгляд, который пронизал

меня до глубины Души. Меня это тут же сбило с толку и я не мог

продолжать свою хвалебную речь о себе же. Так закончилась наша встреча,

однако он оставил надежду. Он сказал, что может быть я смогу навестить

его в его доме когда-нибудь.

Мне было трудно оценить действие, которое оказал взгляд Дон Хуана на

меня, и уникальность того события. Когда я начал изучать антропологию

и, таким образом, встретил Дон Хуана, я уже был знатоком того "как

сориентироваться в обстановке". Дом я оставил годами раньше и это, по

моим оценкам, значило, что я могу сам о себе позаботиться. Как только

мне отказывали, обычно я мог добиться лестью своего желания, делать

уступки, спорить, злиться, но если ничего не помогало, я ныл и

жаловался; другими словами, всегда было что-то, что я знал и делал в

зависимости от обстоятельств, и никогда в моей жизни, ни один человек

не мог остановить меня настолько быстро и явно, как это сделал Дон Хуан

в тот полдень. Дело было не только в том, что меня заставили замолчать;

были времена, когда я не мог сказать ни слова своему противнику, потому

что чувствовал внутреннее уважение к нему, и всё же моя злость или

досада отражалась в моих мыслях. Однако, взгляд Дон Хуана сковал меня

до такой степени, что я не мог толком думать. Меня этот ошеломляющий

взгляд сильно заинтриговал и я решил его найти. После той первой встречи, я готовил

себя 6 месяцев, перечитал всё на использование peyote среди американских иодейцев,

особенно о культе peyote

среди индейцев Равнин.

Я ознакомился с каждой имеющийся работой и когда я почувствовал, что

готов, я поехал обратно в Аризону.

Суббота, 17 декабря 1960. Я нашёл его дом после наведения долгих,

излишних справок среди местных индейцев. Было поздее утро когда я

прибыл и припарковался перед домом. Я увидел его сидящим на деревянном

ящике из-под молока. Он, похоже, узнал меня и поприветствовал, когда я

вылез из машины. Мы

обменялись обычными приветствиями и затем, простыми словами я

признался, что с моей стороны, я обошёлся с ним по-дьявольски, когда мы

встретились впервые. Я тогда хвалился, что много знал о peyote, когда на самом деле, я ничего о нём

не знал. Он уставился на меня, глаза были очень добрые. Я сказал ему,

что я шесть месяцев читал, чтобы подготовить себя к нашей встрече, и

что на этот раз я действительно знаю намного больше. Он рассмеялся.

Похоже, было что-то в моём заявлении, что рассмешило его. Он рассмеялся

надо мной и я немного смутился и обиделся. Он видимо, заметил моё

смущение и заверил меня, что хоть у меня и хорошие намерения, но

реально, не было возможности подготовиться к нашей встрече. Я не знал,

будет ли уместно спросить, имело ли это заявление какой-то тайный

смысл, но не спросил; и всё же он, похоже, понимал мои чувства и

продолжил объяснять то, что имел ввиду. Он сказал, что мои попытки

напомнили ему историю о людях, которых один король однажды осудил и

убил. Он сказал, что в истории осуждённая пара не отличалась от своих

судей, кроме как они настаивали на произношение определённых слов в

странной манере, подходящей только им; та ошибка, конечно, была знаком,

ключевым словом. И король поставил посты в

критических местах, где официальный представитель просил каждого

проезжающего мужчину произнести ключевое слово. Те, кто мог

произнести его так, как король, оставались в живых, а те, кто не мог,

тут же убивались. Суть истории была в том, что однажды молодой человек

решил подготовить себя, чтобы пройти через пост, научившись произносить

ключевое слово так, как это

любил король. Дон Хуан сказал, широко улыбнувшись, что молодому человеку взяло шесть

месяцев, чтобы научиться такому произношению. А когда пришёл день великого

экзамена, молодой человек очень уверенно пошёл на пост и дождался когда официальный представитель

попросит его произнести это слово.

20-21

В этот момент Дон Хуан многозначительно остановил свой рассказ и

посмотрел на меня. Его пауза была очень продуманной и казалась немного

хитрой для меня, но я подыгрывал: я уже слышал эту историю раньше. Она

была связана с евреями в Германии и как можно было отличить евреев по

тому, как они произносили определённые слова. Я также знал финал

истории: молодой человек будет пойман, потому что представитель забыл ключевое слово и попросил его

произнести другое слово, которое было очень похоже, но которое молодой

человек не выучил, как правильно сказать. Дон Хуан похоже ждал, когда я

спрошу, что случилось, ну я и спросил.

"Что с ним случилось?" спросил я, стараясь выглядеть наивным и

заинтересованным в истории.

"Молодой человек, кто был настоящей лисой," сказал он, "понял, что

представитель забыл ключевое

слово, и не успел человек ничего сказать, как сознался, что готовился

шесть месяцев." Он ещё

сделал паузу и посмотрел на меня с озорным огоньком в глазах. В этот

раз он выиграл. Признание молодого человека был новый элемент и я

больше не знал, как заканчивается история.

"Ну и как всё закончилось?" спросил я с интересом.

"Молодой человек конечно был тут же убит," сказал он и покатился от

хохота. Мне очень понравилось как он заинтриговал меня; но больше всего

мне понравилось, как он связал эту историю с моим собственным случаем.

Видимо, он придумал её, чтобы связать со мной. Он смеялся надо

мной в очень лёгкой, артистичной манере и я смеялся вместе с ним.

Впоследствии я сказал ему, что неважно как глупо я выглядел, мне

действительно интересно было изучить кое-что о растениях.

"Я люблю много ходить," сказал он. Я подумал, что он нарочно меняет

тему разговора, чтобы мне не отвечать. Я не хотел настраивать его

враждебно своим упрямством. Он спросил меня, хочу ли я пойти с ним

ненадолго в пустыню. Я ответил, что к прогулке в пустыне я охотно присоединюсь.

"Это не будет пикник," предупредил он меня. Я ответил, что хотел бы

очень серьёзно работать с ним, но мне нужна информация, любая

информация на использование медицинских трав. И что я хочу платить ему

за это.

"Ты будешь работать на меня и я буду платить тебе зарплату," сказал я.

"Сколько ты будешь мне платить?" спросил он и я заметил оттенок

жадности в его голосе.

"Что ты считаешь подходящим," сказал я.

"Плати за моё время...своим временем," сказал он. Я подумал, что он был

очень странным человеком, и сказал ему, что не понял его. Он ответил,

что сказать о растениях нечего, поэтому брать с меня деньги нет смысла.

Он пронзил меня взглядом. "Что ты делаешь в своём кармане?" спросил он

нахмурившись. Он имел ввиду то, что я писал на крошечном блокноте

внутри огромных карманов моей куртки. Когда я сказал ему, что я делал,

он от души посмеялся. Я сказал ему, что не хотел огорчать его и писать

на виду. "Если хочешь писать, то пиши," сказал он. "Ты мне не мешаешь."

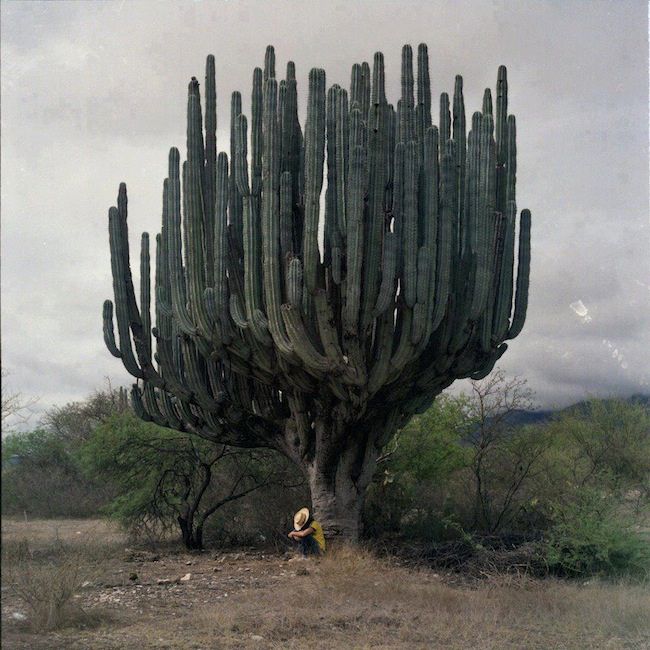

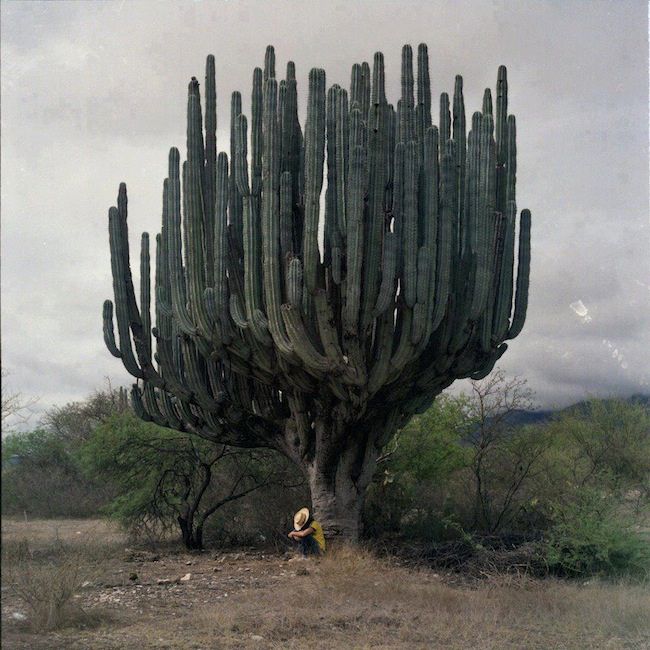

Мы походили по пустыни почти до темноты. Он не показал мне никаких

растений и о них вообще не говорил. Мы остановились на момент, чтобы

отдохнуть у больших кустов. "Растения - очень загадочные существа,"

сказал он, не глядя на меня. "Они - живые и они чувствуют." В тот

момент, когда он это сказал, сильный порыв ветра тряхнул кусты вокруг

нас и кусты произвели раскатистый шум. "Ты это слышишь?" спосил он

меня, приставляя правую руку к уху, как-будто это помогало слышать.

"Ветер и листья согласны со мной."

22-23

Я засмеялся. Друг, который нас познакомил, уже предупредил меня

следить, потому что старик был эксцентрик. Я подумал, что "согласие

листьев" и было одной из его странностей. Мы ещё походили, но он всё

ещё не рвал и не показывал мне растения. Он просто плыл через кусты,

мягко трогая их, потом остановился, сел на камень и предложил мне

отдохнуть и посмотреть вокруг. Я настаивал на разговоре и опять

напомнил ему, что очень хотел бы изучить растения, особенно peyote. Я умолял его стать моим наставником

в обмен на денежное вознаграждение.

"Тебе не нужно платить мне," сказал он. "Ты можешь спросить меня всё,

что хочешь и я скажу тебе, что с этим нужно делать." Он спросил,

подходит ли мне

такой расклад дел, и я был рад. Затем он добавил загадочное заявление.

"Наверно о растениях ничего не изучишь, потому что о них нечего

сказать." Я не понял, что он сказал или что он имел ввиду.

"Что ты сказал?" спросил я и он повторил то же самое 3 раза, и тогда

весь район затрясся от грохота, низко летящего, самолёта.

"Вот! Мир только что со мной согласился." сказал он, прислонив свою

левую руку к уху. Я находил его очень занимательным: его смех

заразительным.

"Ты из Аризоны, Дон Хуан?" спросил я, стараясь продолжать разговор в

основном вокруг него быть моим просветителем. Он смотрел на меня и

утвердительно кивал, глаза выглядели усталыми, я мог видеть белое под

его зрачками. "Ты родился в этой местности?" Он кивнул головой и снова

мне не ответил. Это казалось утвердительным жестом, но также это было

похоже на нервный кивок человека в процессе мышления.

"А ты сам откуда будешь?" спросил он.

"Я - из Южной Америки," сказал я.

"Это большое место, ты пришёл из всего этого?" его глаза опять пронзили

меня. Я начал объяснять обстоятельства моего рождения, но он перебил

меня. "В этом отношении мы похожи," сказал он. "Сейчас я живу здесь, но

я - Яки из Соноры."

"Неужели! Я сам происхожу из..." он не дал мне закончить.

"Я знаю, я знаю," сказал он. "Ты тот, кто есть, откуда-нибудь, как я - Яки из Соноры." Его глаза сверкали и смех странно

беспокоил. Он заставил меня подумать, что поймал меня на лжи: я ощутил

странное чувство вины и чувство, что он

знает то, что не знаю я или не хочет мне сказать. Моё странное смущение

росло и он наверно это заметил, так как он встал и предложил пойти

поесть в ресторан в городе. Он сказал, что никогда не пьёт даже пиво. Я

втихоря смеялся, не веря ему; приятель, кто нас познкомил, сказал мне,

что "старик - не в своём уме большую часть времени." Я реально не

возражал, если он врал мне о том, что не пьёт. Мне он нравился; в нём

было что-то успокающее. На моём лице должно быть было сомнение,

так как он начал объяснять, что он пил в молодости, но однажды просто

бросил.

"Люди едва понимают, что мы можем выбросить всё из наших жизней в любое

время вот так," и щёлкнул пальцами.

"Ты думаешь, что любой может остановиться пить и курить так легко?"

спросил я.

"Конечно!" сказал он совершенно убеждённо. "Курение и алкоголь - ничто,

если мы хотим это бросить." В этот момент кипящая вода в кофейнике

сделала громкий свистящий звук.

"Слышишь это!" воскликнул Дон Хуан с блеском в глазах. "Кипящая вода со

мной согласна." Затем после паузы добавил, "Человек может получить

согласие от всего вокруг себя." В этот критический момент кофейник

пёрнул. Он посмотрел на кофейник и тихо сказал, "Спасибо," кивнул

головой и закатился громовым хохотом.

Я опешил: его смех был слишком громким, но меня реально развлекало всё

это. Моя первая настоящая сессия с моим "наставником" так и

закончилась:

он попрощался в дверях ресторана. Я сказал ему, что мне

нужно посетить друзей и что мне хотелось бы снова его увидеть в конце

следующей недели.

"Когда ты будешь дома?" спросил я, он всмотрелся в меня и ответил,

"Когда ты придёшь."

"Я точно не знаю, когда я смогу придти."

"Тогда просто приди и ни о чём не беспокойся."

"А что если тебя дома нет?"

"Я буду дома," сказал он, улыбаясь и ушёл. Я побежал за ним и спросил

его, будет ли он возражать, если я принесу фотоаппарат с собой и сниму

его и его дом.

"Это - невозможно," сказал он, нахмурившись.

"А как насчёт магнитфона? Это тоже нельзя?"

"Думаю, это тоже невозможно." Я рассердился и сказал ему, что не вижу

логики в его отказе. Дон Хуан тряхнул головой в знак несогласия.

"Забудь об этом, и если ты всё ещё хочешь видеть меня, то никогда об

этом не упоминай." Произнёс он очень убедительно. Я выдал, наконец,

финальную жалобу и сказал, что фото и магнитофонные записи были

необходимы в моей работе. Он сказал, что есть только одна вещь, которая

необходима для всего, что мы делаем, и назвал это - 'Spirit-Дух'.

"Нельзя обойтись без Духа," сказал он. "И у тебя его нет. Тебе об этом

нужно беспокоиться, а не о фото."

"Что ты...?" Он перебил меня движением своей руки и отошёл на несколько

шагов назад. "Не забудь вернуться," тихо сказал он и помахал на

прощанье.

2. СТИРЕТЬ ИСТОРИЮ

СВОЕЙ ЖИЗНИ

26-27

Четверг, 22 декабря 1960.

Дон Хуан сидел на полу у двери своего дома спиной к стене. Он

перевернул ящик из под молока, попросил меня сесть и чувствовать себя

как дома. Я предложил ему сигареты: я привёз целую коробку. Он сказал,

что не курит, подарок взял. Мы поговорили о холодных ночах в пустыне и

других обычных вещах. Я спросил его, не мешаю ли я его обычным делам.

Он посмотрел на меня, нахмурившись, и сказал что у него привычной

рутины не было, и что я могу остаться с ним весь день, если захочу. Я

приготовил кое-какие генеологические таблицы, которые мне хотелось

заполнить с его помощью. Я также вытащил из этнографической литературы

длинный список черт культуры, которые свидетельствовали о

принадлежности к индейцам этого района. Мне хотелось пройти список с

ним и отметить все вещи, которые были знакомы ему. Я начал с таблиц о

родственных связях.

"Как ты называл своего отца?" спросил я его.

"Я называл его отец," ответил он с очень серьёзным выражением лица. Я

почувствовал лёгкое раздражение, но продолжал, полагая что он не понял.

Я показал ему таблицу и объяснил, что одно место для отца, а другое для

матери. Для примера, я привёл другие слова, используемые для онца и

матери в английском и в испанском. Я подумал, что наверно мне надо было

начать с матери.

"Как ты называл свою мать?" спросил я.

"Я называл её Мам," ответил

он наивным тоном.

"Я имею ввиду, какие другие слова ты используешь, чтобы называть своего

отца и мать?" сказал я, пытаясь быть терпеливым и вежливым. Он почесал

свою голову и тупо посмотрел на меня.

"Ну!" сказал он. "Ты меня поставил в тупик, дай подумать." После

минутного колебания, он похоже, что-то вспомнил, и я приготовился

писать. "Итак," сказал он, как-будто он решал какую-то серьёзную

проблему, "как ещё я их называл? Я говорил им 'эй, отец, эй, мать!' " я

невольно расхохотался. Его выражение лица было таким комичным и в тот

момент я не знал: был он абсурдным стариком, надувающим меня, или он

был просто примитивен. Собрав всё терпение, какое у меня было, я

объяснил ему, что это были очень серьёзные вопросы и что это было очень

важно для заполнения моих форм. Я пытался заставить его понять идею

генеологии и персональной истории.

"Как звали твоего отца и мать?" спросил я, а он посмотрел на меня

чистыми добрыми глазами.

"Не трать время на эту ерунду," сказал он тихо, но с неожиданной силой.

Я не знал, что ответить: это было как-будто кто-то другой произнёс эти

слова. Только секунду назад он был неуклюжий, тупой индеец, чесавший

голову, и вдруг, секундой позже роли поменялись: я был тупым, а он

направил на меня неописуемый взгляд. Это не было вызывающе, с

ненавистью, с презрением или с превосходством. Его глаза были чистыми,

добрыми и проницательными. После долгой паузы

он сказал, "У меня нет личной истории. Однажды я понял, что личная

история мне больше не была нужна, и как алкоголь, я отбросил её." Я не

совсем понял, что он этим имел ввиду. Вдруг мне стало нехорошо: мне

что-то угрожало и я напомнил ему, что он заверил меня в том, что я могу

задавать ему вопросы. Он повторил, что не возражал. "У меня больше нет личной истории,"

сказал он и испытующе посмотрел на меня."

28-29

"Я отбросил это однажды, когда почувствовал, что в этом больше нет

необходимости," я уставился на него, стараясь обнаружить скрытое

значение его слов.

"Как можно отбросить личную историю?" спросил я придирчивым тоном

спорщика.

"Сначала нужно иметь желание отбросить это, а затем нужно производить

это гармонично, понемногу отрезая её."

"Зачем нужно такое желание?" воскликнул я, будучи ужасно привязанным к

своей личной истории: мои семейные узы были крепкими. Я серьёзно

чувствовал, что без них моя жизнь не будет иметь цели и

продолжительности. "Может быть, ты должен сказать мне, что ты имеешь

ввиду под - отбросить

личную историю."

"Обходиться без неё, вот

что я имею ввиду," отрезал он. Я настаивал, что так и не понял в этом

смысла.

"Возьмём тебя, к примеру: ты не можешь изменить то, что ты Яки-индеец."

сказал я.

"Неужели?" спросил он, улыбаясь. "Откуда ты это знаешь?"

"И то правда! Я не могу точно сейчас знать это, но ты это знаешь и это

засчитывается. Это то, что создаёт личную историю." Я почувствовал, что

глубоко пронзил его.

"Тот факт, что я знаю Яки-индеец

я или нет, не делает личную историю," ответил он. "Только когда кто-то

ещё знает это, тогда это становится личной историей.

И я уверяю тебя, что никто никогда этого точно знать не будет." Я

мешковато записал то, что он сказал, остановился и посмотрел на него. Я

не мог его понять, ментально пробегая через все свои впечатления. Его

мистический и неподражаемый взгляд в нашу первую встречу; очарование, с

которым он утверждал, как он получал подтверждение от всего вокруг

него; его раздражающий юмор и его бдительность, проворство,

настороженность, живость; его вид настоящей тупости, когда я спрашивал

его о его отце и матери; и, наконец, неожиданная сила его заявлений,

которая разрубила меня напополам. "Ты же не знаешь кто я, не так ли?"

сказал он, как-будто он читал мои мысли. "Ты никогда не будешь знать

кто и что я, потому что у меня нет личной истории." Спросил, был ли у

меня отец, я сказал, что был. Он сказал, что мой отец был примером

того, что он имел ввиду. Он

настаивал на том, чтобы я вспомнил то, что мой отец думал обо мне.

"Твой отец знает всё о тебе, так что он сделал свои выводы, знает кто

ты, чем занимаешься, и ничто не заставит его изменить его мнение о

тебе." Дон Хуан сказал, что все, кто меня знает, имеют своё мнение обо

мне, и что я продолжал поддерживать это мнение всем тем, что я делал.

"Разве ты не видишь?" сказал он, драматизируя. "Ты должен обновить свою

личную историю, говоря своим родителям, друзьям и родственникам всё,

что ты делаешь. С другой стороны, если у тебя нет личной истории,

объяснения не нужны; никто не сердится и не разочарован твоими

действиями. И самое главное, никто не найдёт тебя своими мыслями."

Вдруг, идея прояснилась в моём мозгу: я почти сам это знал, но никогда

это не обдумывал. Не иметь личную

историю - действительно было привлекательно, по крайней мере на

интеллектуальном уровне. Однако, это дало мне чувство одиночества,

которое я нашёл угрожающим. Мне хотелось обсудить с ним мои чувства, но

я себя контролировал; было что-то ужасно несоответствующее с окружающим

миром в настоящей ситуации. Я чувствовал себя нелепо, стараясь

ввязаться в философский спор со старым индейцем, кто явно не имел 'утончённости' студента универститета. Каким-то

образом он увёл меня от моего первоначального намерения: расспросить

его о его генеологии.

"Я не знаю, как мы вдруг стали говорить об этом, когда всё, что я

хотел, это несколько имён для моей таблицы," сказал я, пытаясь

перевести разговор обратно на эту тему.

"Это очень просто: потому что я сказал, что задавать вопросы о чьём-то

прошлом, это - ерунда." Его тон был твёрдым, и я подумал, что не было

смысла заставлять его менять его мнение, так что я поменял тактику.

"Эта идея - не иметь личную историю - то, что Яки делают?" спросил я.

"Это то, что делаю я."

"Где ты этому научился?"

"Я научился этому в течение моей жизни."

"Твой отец научил тебя этому?"

"Нет. Скажем, что я сам этому научился, а сейчас я собираюсь отдать

тебе этот секрет, так чтобы ты не ушёл отсюда с пустыми руками." Он

снизил голос до драма-

шёпота. Я рассмеялся над его театральными ужимками. Мне пришлось

признать, что он был в этом мастером, и в голову пришла мысль, что я

находился в присуствии прирождённого актёра. "Запиши это: почему нет?

Ты чувствуешь себя более комфортно, когда пишешь." Я посмотрел на него

и мои глаза должно быть выдали моё смущение. Он хлопнул себя по бокам и

с большим удовольствием расхохотался. "Самое лучшее - это стиреть всю

личную историю," сказал он медленно, как бы давая мне время записать

это моим неуклюжим путём, "потому что

это освободит нас от мешающих мыслей других людей." Я не мог поверить,

что он реально говорил это, момент моего замешательства он должно быть

прочёл на моём лице и тут же использовал это. "Возьми себя, например,

ты ведь не знаешь прямо сейчас, ты приходишь или уходишь. И это так,

потому что я стёр мою личную историю. Мало-помалу, я создал туман

вокруг себя и моей жизни. И сейчас, никто не знает кто я и что я делаю."

"Но ты сам знаешь, кто ты, не так ли?" вставил я.

"Поспорим...я не знаю," высказался он и покатился по полу, смеясь над

моим удивлённым взглядом...Его обманчивая тактика уж очень была

угрожающей, я даже испугался. "Это - маленький секрет я собираюсь отдать тебе сегодня," сказал он низким голосом. "Никто не

знает мою личную историю, никто не знает кто я и что

я делаю, даже я сам." Он прищурил глаза, смотрел не на меня, а через моё правое плечо. Он

сидел, скрестив ноги, его спина была прямой и всё же он казался таким

спокойным. В этот момент он представлял собой настоящую картину Силы. Я

воображал его индейским вождём, "краснокожим воином" в романтических

историях моего детства.

Мой романтизм унёс меня

прочь и необычайно коварное противоречивое чувство обуяло меня. Я мог

откровенно сказать: он мне очень нравился и, в то же время,

я мог сказать, что я его смертельно боялся. Он сохранял тот пристальный

взгляд долгое время. "Как могу я знать, кто я, когда я всё это?" сказал

он, обводя головой окружающий мир. Потом он посмотрел на меня и

улыбнулся. "Мало-помалу ты должен создать туман вокруг себя; ты должен

стиреть всё вокруг себя, пока ничто не может быть взято как должное,

пока ничто больше не реальное. Твоя проблема сейчас, что ты слишком

реальный, твои достижения слишком очевидны, твой настрой слишком виден.

Не бери вещи как должное, ты должен начать стирать себя."

"Для чего?" спросил я враждебно. Тогда мне стало ясно, что он советует

мне, как себя вести. За всю свою жизнь я достиг точки, когда кто-то

пытается говорить мне, что делать; сама мысль, что мне говорят, что

делать, тут же враждебно настраивает меня.

"Ты сказал, что хочешь изучить растения," спокойно сказал он. "Ты

хочешь получить что-то просто так? Что ты думаешь это? Мы договорились,

что ты будешь задавать мне вопросы и я скажу тебе то, что знаю. Если

тебе это не нравится, тогда нам не о чем говорить." Его ужасная прямота

и зависть раздражали меня и

я должен был признать, что он прав. "Тогда давай посмотрим на это так,"

продолжал он. "Если ты хочешь узнать больше о растениях, хотя о них

реально ничего не скажешь, ты должен, помимо других вещей, стиреть свою

личную историю."

"Как?" спросил я.

"Начни с простых вещей, как например, не рассказывай то, что ты

действительно делаешь. Затем ты должен покинуть тех, кто хорошо тебя

знает. Таким образом,

ты создашь туман вокруг себя."

32-33

"Но это абсурдно," запротестовал я. "Почему люди не должны меня знать?

Что в этом плохого?"

"Что неправильно, так это то, что как только они тебя узнают, ты

становишься предметом, которым можно пользоваться, и с этого момента ты

не сможешь сломать связь с их мыслями. Мне лично нравится полная

свобода быть незнакомым. Никто не знает меня с непоколебимой

уверенностью, так как люди знают тебя, например."

"Но это будет обманом."

"Меня не интересует ложь или правда," сказал он серьёзно. "Ложь -

только ложь, если у тебя имеется личная история." Я спорил, что мне не

нравилось намеренно мистифицировать людей и вводить их в заблуждение.

Его ответ был, что я ввожу в заблуждение всех так или иначе. Старик

затронул моё больное место в жизни.

Я тут же спросил его, что он этим имел ввиду или как он узнал, что я

всё время мистифицирую людей. Я просто среагировал на его заявление,

защищая себя с помощью объяснения. Я сказал, что с болью сознаю, что

моя семья и мои друзья верили, что мне нельзя доверять, когда на самом

деле, я никогда в жизни не врал.

"Ты всегда знал как врать,"

сказал он. "Единственное, что отсуствовало, было то, что ты не знал,

зачем это делать, а сейчас ты знаешь."

Я запротестовал. "Разве ты не видишь, что мне смертельно надоело, что

люди думают: я не надёжный?" сказал я.

"Но ты - ненадёжный," убедительно ответил он.

"Будь всё проклято, это не так," воскликнул я: моё настроение вместо

того, чтобы сделать его серьёзным, навлекло на него приступ

истерического смеха. Я реально ненавидел старика за всю эту хрень. К

сожалению, он был прав насчёт меня. Через некоторое время я успокоился

и он продолжил разговор.

"Когда личная история отсуствует," объяснял он, "ничего, что человек

говорит, не может быть принято за ложь. Твоя проблема в том, что тебе

приходиться объяснять всё всем принудительно, и в то же время ты хочешь

сохранять свежесть, новизну того, что ты делаешь. Ну, а так как тебя не

волнует объяснение всего, что ты сделал, ты врёшь, чтобы всё

продолжалось." Я реально был поражён масштабом нашего разговора и

записал все детали нашего обмена фразами лучшим путём, на какой был

способен, концентрируясь на том, что он говорил, и не останавливался,

чтобы распространяться о моих предрассудках или на его значениях.

"С сегодняшнего дня, ты должен просто показывать людям то, что хочешь

показать им, но никогда не говоря точно, как ты это сделал."

"Я не могу хранить секреты!" воскликнул я. "То, что ты говоришь, для

меня бесполезно."

"Тогда поменяйся!" отрезал он со свирепым блеском в глазах. Он выглядел

как странное дикое животное. И всё же, он был таким связанным в своих

мыслях и таким разговорчивым. Моя досада перешла в состояние

раздражительного замешательства. "Понимаешь," продолжал он, "у нас

имеется только два выбора: или мы принимаем всё за настоящее, или мы не

принимаем. Если мы следуем первому, мы придём к тому, что нам

смертельно надоест мир и мы сами. Если мы последуем второму и сотрём

личную историю, мы создадим туман вокруг себя, очень волнующее и

мистическое состояние, в котором никто не знает, откуда выпрыгнет заяц."

Я продолжал спорить, что стирев личную историю, только увеличит наше

чувство незащищённости. "Когда

ничто не убеждает, мы круглогодично делаемся настороже," сказал он.

"Больше волнует - не знать за каким кустом прячется заяц, чем вести

себя как-будто мы всё знаем."

Он не сказал больше ни слова очень долгое время; наверно час прошёл в

полном молчании. Я не знал, что спросить. Наконец он встал и попросил

меня отвезти его в близлежайший городок. Я не знал почему, но наш

разговор вытащил из меня энергию. Мне хотелось спать. Он попросил меня

остановиться по пути и сказал мне: если я хочу отдохнуть, то мне

придётся залезть на плоскую вершину небольшого холма у дороги, и лечь

животом вниз, головой на восток. Похоже в нём было ощущение срочности.

Мне не хотелось спорить или наверно я слишком устал, чтобы говорить. Я

залез на холм и и сделал, как он посоветовал.

34

Я проспал только 2-3 минуты, но этого было достаточно, чтобы вернуть

мою энергию. Мы поехали в центр городка, где он попросил меня его

сбросить.

"Возвращайся," сказал он, выходя из машины. "Обязательно, возвращайся!"

3. ПОТЕРЯ МАНИИ ВЕЛИЧИЯ

35

У меня была возможность обсудить мои два предыдущих визита к Дон Хуану

с тем другом, кто меня с Дон Хуаном познакомил. По его мнению, я

напрасно терял время. Я пересказал ему во всех деталях все наши

разговоры. Он подумал, что я преувеличиваю и приукрашиваю глупые старые

привычки. Для романтизма в таком глупом старикане у меня не было места.

Я искренне чувствовал, что его критика моей личности серьёзно подорвала

моё отношение к нему. Однако, мне пришлось признать, что его замечания

всегда были в точку, остро обрисовывали и были правдивы. Корень моей

проблемы в тот момент было моё нежелание принять то, что Дон Хуан был

очень способен разбить все мои предубеждения в отношении мира, и моё

нежелание соглашаться с моим другом, кто думал, что "старик был

сумасшедшим". Это заставило меня посетить его ещё раз, прежде чем я

решился.

Среда, 28 декабря 1960.

Тут же после прибытия в его дом, он взял меня на прогулку в пустыню. Он

даже не посмотрел на пакет продуктов, который я привёз. Похоже он ждал

меня. Ходили часами, но он не собирал и не показывал мне никаких

растений. Однако он учил меня "подходящей походке". Он сказал, что я

должен слегка сгибать свои пальцы во время ходьбы, так я буду сохранять

своё внимание на тропинке и на окружающем мире.

36-37

Он утверждал, что моя обычная походка ослабляла, и что никогда не нужно

ничего носить в руках. Если вещи нужно нести, то использовать рюкзак

или плечевой мешок/сетку. Его идея была, что принятие руками особого

положения, способствует огромной выносливости и осознанности. Я не

видел причин для споров и согнул пальцы, как он посоветовал, и

продолжал идти. Моё сознание никак не поменялось и также моя

выносливость. Мы начали ходьбу утром и остановились отдохнуть около

полудня. Я вспотел и хотел попить воды из моей фляшки, но он остановил

меня, сказав, что лучше выпить только глоток. Он срезал какие-то листья

с небольшого жёлтого куста и пожевал их, дал мне несколько и заметил,

что они были превосходны, а если я буду жевать их медленно, то моя

жажда исчезнет. Жажда не исчезла, но я чувствовал себя хорошо. Он,

казалось, читал мои мысли и объяснил, почему я не почувствовал

приемущества "правильной походки" и "жвачки листьев", потому что я был

молод и силён, и моё тело ничего не заметило, потому что оно было

немного глупым. Он засмеялся, но мне было не до смеха и это доставило

ему ещё больше удовольствия. Он поправил своё высказанное заявление

сказав, что моё тело, по правде, не было глупым, а каким-то спящим.

omen!

omen!

В этот момент, огромная ворона, каркая, пролетела прямо над нами. Это

изумило меня и я начал смеяться. Я думал, что над таким стоит

посмеяться, но, к моему удивлению, он сильно тряхнул мою руку и

поторопил меня встать. Его выражение лица было очень серьёзным. "Это не

было шуткой," сказал он резко, как-будто я знал, о чём он говорил, и

попросил объяснить. Я сказал ему, что это не сочеталось с окружающей

обстановкой, что мой смех над вороной рассердил его тогда, как мы

смеялись над кофейником.

"То, что ты видел, не было просто вороной," воскликнул он.

"Но я видел её и это была ворона," настаивал я.

"Ты ничего не видел, дурак," сказал он сурово. Его грубость мне не

понравилась. Я сказал ему, что мне не нравится сердить людей, и что

наверно мне лучше уйти, так как он был не в настроении иметь компанию.

Он раскатисто рассмеялся, как-будто я был клоуном, исполняющим роль для

него. Моё раздражение и смущение росло не по дням, а по часам. "Ты

очень жестокий," прокомментировал он между прочим. "Ты относишься к

себе слишком серьёзно."

"А ты - не делал то же самое?" вставил я. "К себе ты разве не относился

слишком серьёзно, когда рассердился на меня?"

Он сказал, что рассердиться на меня, было последняя вещь в его голове.

Он проницательно посмотрел на меня. "Что ты видел, не было в согласии с

миром," сказал он. "Летящие или каркающие Вороны - это ОМЕН !"

"Омен чего?"

"Твой очень важный знак," мистически произнёс он. В этот самый момент

ветер скинул сухую ветвь дерева прямо к нашим ногам. "Вот это

согласие!" воскликнул он, посмотрел на меня сверкающими глазами и

залился хохотом. У меня было такое чувство, что он дразнил меня,

фабрикуя правила своей странной игры, пока мы двигались, поэтому ему

было хорошо смеяться, но не мне. Моё раздражение наростало и я высказал

ему то, что о нём думал, но он не рассердился и не обиделся. Он смеялся

и его смех меня разозлил и расстроил ещё больше. Я подумал,

что он нарочно издевается надо мной и решил прямо на месте, что с меня

хватит "полевой работы". Я встал и сказал, что хочу идти назад к его

дому, потому что мне нужно уехать в Лос Анжелес.

"Сядь!" повелительно сказал он. "Ты раздражаешься как старуха. Ты не

можешь уйти сейчас, потому что мы ещё не закончили." Я его ненавидел,

считал неприятным человеком. Он начал петь идиотскую мексиканскую

песню, явно имитируя одного популярного певца. Он удлинял кое-какие

гласные и сокращал другие, так сделал из песни неимоверно смешную

пародию. Она была настолько комична, что я невольно расхохотался.

"Видишь, ты можешь смеяться над дурацкой песней," сказал он.

38-39

"Но человек, так поющий её, и те, кто платит, чтобы его слушать, не

смеются: они думают, это серьёзно."

"Что ты имеешь ввиду?" спросил я. Я подумал, что он нарочно придумал

пример сказать мне, что я смеялся над вороной, потому что я не принял

это серьёзно, точно также как я не отнёсся серьёзно к песне. Но он

снова меня поставил в тупик. Он сказал, что я был как певец и как люди,

кому нравились его песни, имеют слишком высокое мнение о себе и

невероятно серьёзны о чепухе, на которую никто в здравом уме не

польстится. Потом он повторил, как бы освежить мою память, всё, что он

сказал до этого на тему "изучение растений". Он с ударением подчеркнул:

если я действительно хотел научиться, то мне придёться изменить большую

часть моего поведения. Моё раздражение росло до тех пор, пока я с

огромным трудом мог даже делать записи.

"Ты относишься к себе слишком серьёзно," сказал он медленно. "Ты

думаешь, что ты чертовски важный. Это нужно поменять! Ты настолько

чертовски важный, что чувствуешь правильным всему раздражаться. Ты

настолько выпендриваешься, что ты можешь позволить себе уйти, если

обстановка для тебя не будет складываться хорошо. Думаешь, что это

показывает наличие у тебя характера? Ерунда! Ты слаб и о себе высокого

мнения!" Я пытался протестовать, но он не поддался. Он указал, что за

всю свою жизнь я никогда ничего не закончил из-за чувства своего превосходства,

которое я на себя повесил. Я был ошеломлён точностью его заключений.

Конечно это было правдой и это не только разозлило меня, но и

превратилось в угрозу. "Мания Величия - ещё одна вещь, которая должна

быть анулирована, также как и личная история," сказал он драматическим

тоном. Я явно не хотел с ним спорить: итак было ясно, что я ужасно

проигрываю. Он и не собирался идти домой, пока не был готов, а я не

знал путь назад, пришлось остаться с ним. Он сделал странное и

неожиданное движение, нюхая воздух вокруг него, его голова слегка

ритмично тряслась. Казалось, он был в состоянии необычной

настороженности, повернулся и уставился на меня с любопытством и

недоумением. Его глаза осматривали моё тело сверху донизу, как-будто он

искал что-то особенное, потом он резко встал и начал быстро шагать. Он

почти бежал и я следовал за ним. Он сохранял очень большую скорость

почти час,

наконец, он остановился у каменистого склона и мы сели в тени кустов.

От быстрой ходьбы я полностью обесилел, хоте настроение улучшилось.

Было странно как я

поменялся: я был в приподнятом настроении, а перед ходьбой, после

нашего спора, я был зол на него.

oмен!

oмен!

"Это очень странно," сказал я, "но я чувствую себя очень хорошо." Я

услышал карканье вороны вдали, он поднял палец к правому уху и

улыбнулся.

"Это был омен," сказал он. Небольшой камень с раскатистым ударом

скатился вниз, приземлившись в кустах. Он громко засмеялся и указал

пальцем в направлении звука. "А это было согласие," сказал он. Затем он

спросил меня, был ли я готов обсудить мою Манию Величия. Я засмеялся;

моё чувство злости казалось так далеко от меня, что я даже не мог

представить себе, как я мог быть зол на него.

"Я не пойму, что со мной

происходит," сказал я. "Я разозлился, а сейчас я не знаю, почему я

больше не злюсь."

"Мир вокруг нас очень мистический и он свои секреты легко не отдаёт,"

сказал он и мне нравились его загадочные и вызывающие высказывания. Я

не мог понять, были ли они наполнены скрытым смыслом или это была

просто бессмыслица. "Если ты когда-нибудь вернёшься в эту пустыню,

сторонись того каменистого холма, где мы останавливались сегодня.

Избегай его как заразу, " сказал он.

"Почему? В чём дело?"

"Сейчас не время объяснять,

сейчас нас больше интересует потеря Мании Величия. Пока ты будешь

чувствовать, что ты самое важное в мире, ты не сможешь по настоящему

оценить мир вокруг себя. Ты

- как лошадь с шорами на глазах, всё, что ты видешь, это - себя, вдали

от всего остального."

40-41

Какой-то момент он осматривал меня. "Я собираюсь поговорить с моим

маленьким другом здесь," сказал он, указывая на небольшое растение. Он

встал перед ним на колени и начал ласкать его и говорить с ним. Сначала

я не понял, что он говорил, но потом он поменял язык и говорил с

растением на испанском. Какое-то время он произносил галиматью, потом

встал. "Неважно что ты скажешь растению,

ты можешь даже придумать слова; что важно, так это чувство

благожелательности к нему и отношение как к равному." Он объяснил, что

человек, который собирает растения, должен каждый раз извиняться за то,

что он их срывает, и должен заверить их, что когда-нибудь его

собственное тело будет служить пищей для них. "Таким образом, растения

и мы - на равных," сказал он. "Ни мы, ни они более или менее важны.

Давай, поговори с растением," подзадоривал он меня. "Скажи ему, что ты

больше не чувствуешь себя важным." Я только смог заставить себя встать

на колени перед растением, но не мог сказать ни слова. Я чувствовал

себя нелепо и засмеялся, однако я не был зол. Дон Хуан потрепал меня по

спине и сказал, что уже хорошо, что я, по крайней мере, справился со

своим характером. "С сегодняшнего дня, говори с небольшими растениями.

Говори, пока не потеряешь всю важность. Говори до тех пор, пока ты не

сможешь делать это перед другими людьми. Иди в те холмы, вон там и

практикуйся." Я спросил, будет ли достаточно разговариваь с ними молча.

Он засмеялся и постучал по моей голове. "Нет! Ты должен говорить с ними

громким и ясным голосом, ели ты хочешь, чтобы они тебе ответили."

Я пошёл туда, куда он указал, посмеиваясь наедине над его

эксцентричностью. Я даже пытался говорить с растениями, но моё ощущение

нелепости положения меня подавляло. После достаточно долгого

отсуствия, как я полагал, я пошёл назад туда, где был Дон Хуан. Я был

уверен, что он знал: с растениями я не разговаривал. На меня он даже не

взглянул, только посигналил мне сесть рядом.

"Наблюдай за мной внимательно, я собираюсь поговорить с моим маленьким

другом." Он встал на колени перед маленьким растением и несколько минут

двигался и извивал своё тело, болтая и смеясь. Я подумал, что он сошёл

с ума. "Это маленькое растение сказало мне передать тебе, что она -

хороша для еды," сказал он, поднимаясь с колен. "Она сказала, что пучок

их будет держать человека здоровым. Она также сказала, что их несколько

растёт вон там." Дон Хуан указал на склон горы не так далеко. "Пошли,

посмотрим," сказад он, а я рассмеялся над его представлением. Я был

уверен, что он найдёт растения, потому что он был знатоком района

и знал, где находятся съедобные и медицинские травы. Пока мы шли к тому

месту, он сказал мне ненароком, что мне следует обратить внимание на

это растение, потому что оно было съедобным и медицинским. Я спросил

его полушутя: это растение тебе только что сказало. Он остановился и

осмотрел меня, не веря своим глазам, и тряхнул головой из стороны в

сторону, смеясь. "Как может это растение сказать мне сейчас то, что я

знал всю жизнь?" И продолжил объяснять, что он знал полностью разные

свойства этого растения, а оно только сказало ему, что их целая группа

растёт в том районе, куда он указал, и что она не возражала, что он

скажет мне об этом. Прибыв на склон холма, я нашёл целую группу таких

же растений. Мне хотелось смеяться, но он не дал мне времени: он хотел,

чтобы я

поблагодарил группу растений. Мне было стыдно и я не мог заставить себя

это сделать. Он чистосердечно улыбнулся и выдал ещё одно загадочное

высказывание. Он повторил

его 3-4 раза, как бы дать

мне время понять его значение.

42

"Мир вокруг нас - это тайна," воскликнул он. "И мужчины не лучше, чем

любой другой. Если маленькое растение не жалеет для нас, мы должны

благодарить её или, может быть она не позволит нам пройти." То, как он

посмотрел на меня, когда сказал это, бросило меня в холодный пот. Я

поспешил нагнуться над растением и сказал, "Спасибо," громким голосом.

Он залился спокойными, контролируюмыми взрывами смеха. Мы походили ещё

час и затем стали возвращаться в его дом.

В какой-то момент я отстал и ему пришлось ждать меня. Он проверил мои

пальцы: согнул я их или нет. Я не согнул. Он сказал мне настоятельно:

когда я хожу с ним, то мне придётся наблюдать и копировать его жесты

или вообще не приходить.

"Я не могу ждать тебя как-будто ты ребёнок," сказал он порицательным

тоном. Это замечание дошло до самой глубины моего смущения и изумления.

Как это было возможно, чтобы такой старик мог ходить настолько лучше,

чем я? А я то думал, что я в прекрасной атлетической форме и всё же,

ему реально пришлось ждать меня, чтобы я его догнал. Я согнул пальцы и

невероятно: я мог сохранять ту же скорость, как и он, без всяких

усилий. Больше того, временами я чувствовал, что мои руки тянули меня

вперёд. Я был в приподнятом настроении и был вполне счастлив глупо

шагать с этим странным старым индейцем. Я начал разговаривать и

несколько раз попросил его показать мне растение peyote. Он посмотрел на меня, но не

сказал ни слова.

4.

СМЕРТЬ - СОВЕТНИК

43

Среда, 25 января 1961.

"Ты когда-нибудь научишь меня peyote?" спросил я. Он не ответил и, как он

это делал раньше, просто посмотрел на меня, как-будто я сошёл с ума. Я

уже упоминал эту тему в разговорах с ним много раз и каждый раз он

хмурился и качал головой, что не означало ни да, ни нет, это скорее,

был жест отчаяния и удивления.

Он резко встал, мы сидели на земле перед его домом. Едва заметная

тряска головы была приглашением следовать за ним. Мы пошли в кусты

пустыни в южном направлении. По пути он постоянно повторял, чтоя должен

осознавать бесполезность моей Мании Величия и моей личной истории.

"Твои друзья," сказал он, резко поворачиваясь ко мне. "Те, кто знают

тебя долгое время, ты должен быстро с ними распрощаться." Я подумал,

что он сошёл с ума и его настойчивость была идиотской, но я ничего не

сказал. Он уставился на меня и начал смеяться. После долгой ходьбы мы

остановились и я уже собрался сесть, но он сказал мне отойти на 20

метров, поговорить с группой растений громким, ясным голосом. Я был не

в своей тарелке и возбуждён. Его странные требования были больше

невыносимы для меня и я сказал ему ещё раз, что я не могу разговаривать

с растениями, потому что я чувствовал себя дураком. Его единственным

комментарием было, что моё чувство собственного превосходства было

огромным.

Похоже, он вдруг принял решение и сказал, что мне не следует пытаться

говорить с растениями до тех пор, пока я не буду себя чувствовать легко

и естественно с ними. "Ты хочешь изучить их, но не хочешь делать

никакой работы," обвинил он меня. "Что ты стараешься сделать?" Моё

объяснение было: я хотел настоящую информацию об использовании

растений, поэтому я попросил его быть моим советником. Я даже предлагал

платить ему за его время и труд. "Тебе лучше взять деньги," сказал я,

"так мы оба лучше будем себя чувствовать, я тогда смогу просить у тебя

что угодно, потому что ты будешь работать на меня и я буду тебе

платить. Что ты об этом думаешь?" Он посмотрел на меня презрительно и

сделал неприличный звук, вибрируя нижней губой и языком с большой

силой.

"Вот что я думаю об этом," сказал он и истерически расхохотался над

моим удивлённым лицом. Мне было ясно: он был не тот человек, с которым

я бы мог легко дискуссировать. Несмотря на свой возраст, он излучал

энтузиазм и был невероятно силён. У меня была мысль, что будучи таким

старым он мог бы меня прекрасно информировать. Старые люди, как мне

говорили, делались прекрасными советчиками, потому что они были слишком

слабыми, чтобы делать что-то ещё, кроме как болтать. Дон Хуан, с другой

стороны, был неподходящий человек для этой роли. Я чувствовал, что он

был неуправляем и опасен. Друг, который нас познакомил, был прав.

Старик-индеец был эксцентрик; и хотя он ещё не выжил из ума по большей

части, как мне говорил друг, старик был ещё хуже: он был не в своём

уме. Я снова почувствовал ужасные сомнения и беспокойство, которое

испытал

до этого. Я думал, что с этим справился. Собственно у меня совсем не

было проблем убедить себя, что я хочу его опять навестить. Однако,

мысль лезла мне в голову, что наверно я сам был с приветом, когда я

понял, что мне нравилось быть в его компании. Его мнение, что моё

чувство превосходства было препятствием, реально произвело впечатление

на меня. Но всё это наверно было только упражнением в интеллекте с моей

стороны. Момент, когда я предстал перед его странным поведением, я

начал испытывать беспокойство и хотел уйти. Я сказал, что мы были

настолько разными, что сойтись у нас не было возможности.

"Один из нас должен поменяться," сказал он, уставившись в землю. "И ты

знаешь кто." Он начал напевать мексиканскую народную песню, потом резко

поднял голову и посмотрел на меня. Его глаза были неистовы и горели. Я

хотел отвернуться или закрыть глаза, но к моему полному удивлению, я не

мог оторваться от его взгляда. Он попросил меня сказать ему, что я

видел в его глазах. Я сказал, что ничего не видел, но он настаивал,

чтобы я сказал, что его глаза мне напоминают. Я пытался его заставить

его понять, что единственную вещь его глаза

заставили меня осознать, это - моё смущение, и что то, как он смотрел

на меня, было очень неприятно. Он не отставал и продолжал смотреть.

Взгляд не был просто угрожающим или плохим; скорее он был мистическим,

но неприятным.

Он спросил, не напоминает ли он мне птицу.

"Птицу?" воскликнул я. Он хихикнул как ребёнок и отвёл глаза в сторону

от меня.

"Да," сказал он тихо. "Птицу, очень смешную птицу!" Он снова установил

свой взгляд на мне и приказал мне вспомнить. Он говорил с

экстраординарной убедительностью, что он ЗНАЛ, что я видел этот взгляд

раньше. Моё чувство в тот момент было, что старик провоцирует меня

против моего желания, каждый раз когда открывал свой рот. Я уставился

на него в явном поединке. Вместо того, чтобы рассердиться, он начал

смеяться. Он хлопнул себя по бокам и завопил, как-

будто он управлял дикой лошадью. Затем он стал серьёзным и сказал мне,

что было очень важно, чтобы я прекратил бороться с ним и вспомнил ту

смешную птицу, о которой он говорил. "Посмотри в мои глаза," сказал он.

Его глаза были буквально свирепыми, но в них было чувство, которое

реально напоминало мне что-то, но я не был уверен, что это было. С

минуту я обдумывал это и затем меня

вдруг осенило; это не была форма его глаз или форма его головы, а

какая-то холодная свирепость в его взгляде, которая напоминала мне

взгляд фалькона. В момент этого осознания он косо смотрел на меня и на

мгновенье я испытал полный хаос в своей голове.

46-47

Я подумал, что вижу черты фалкона, вместо Дон Хуана. Образ был

мимолётным и я был слишком расстроен, чтобы обратить больше внимания на

него. Очень взволнованным тоном я сказал ему, что мог поклясться: я

видел черты фалькона на его лице. На него напала ещё одна атака смеха.

Я видел взгляд в глазах фальконов, я когда-то охотился на них, когда

был мальчиком, и по мнению моего деда, очень неплохо. У него была

птицеферма, а фалконы были угрозой его бизнесу. Отстреливание их не

только происходило, но и было "правильным". Я забыл, что до этого

момента, эта свирепость в их глазах преследовала меня годами, но это

было так далеко в моём прошлом, что я думал, что память этого потеряна.

"Я охотился на фальконов," сказал я.

"Я это знаю," ответил он как бы случайно. Его тон нёс в себе такую

уверенность, что я начал смеяться, думая, что он был нелепым парнем. Он

имел наглость говорить, как-будто он знал, что я охотился на фалконов.

Я чувствовал огромную неприязнь к нему. "Почему ты разозлился?" спросил

он тоном искренней озабоченности. Я не знал почему и он начал

тестировать меня в очень необычной манере. Он попросил меня снова на

него посмотреть и рассказать ему об "очень смешной птице", которую он

мне напоминал. Я боролся против него и из неприязни сказал, что не о

чем было говорить. Потом я почувствовал желание спросить его, почему он

сказал, что знал : я охотился на фалконов. Вместо ответа он опять

сделал замечание о моём поведении. Он сказал, что я был жестоким

парнем, который был способен взбеситься в один момент. Я протестовал,

что это не было правдой; я всегда думал, что симпатичный и с хорошим

характером. Я сказал, что это была его вина, заставить меня потерять

контроль своими неожиданными словами и действиями.

"Зачем злиться?" спросил он. Я взял себя в руки, мне не следовало на

него злиться. Он снова настоял, чтобы я посмотрел в его глаза и

рассказал ему о "странном фалконе". Он поменял слова: сначала он

говорил "очень смешная птица", потом заменил это на "странный фалкон".

Изменение в словах способствовало изменению моего настроя. Я вдруг стал

печальным. Он так прищурил глаза, что они стали щелями, и сказал